Katy Trail

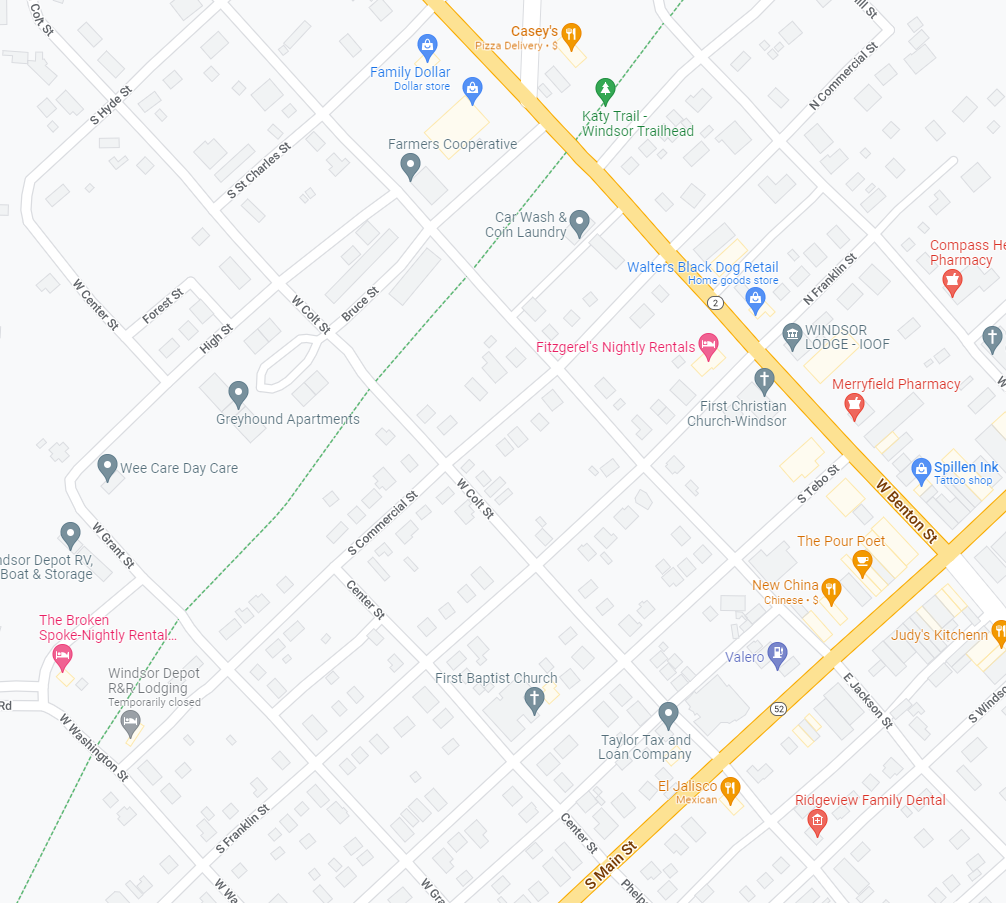

I walked into Windsor, Missouri, about six in the evening, August 10th. I’d left Clinton around half past ten that morning. A caboose that had been donated to the town from the Missouri-Kansas-Texas (MKT) railway after it shut down in the 80s marks the spot of the old depot. I was near the Katy-Rick Junction, where the Rock Island Spur meets the main branch of the Katy Trail. A display by the stranded caboose had a map of the town, telling me You are Here, a few blocks away from Main Street. The trail continued alluringly Northeast off into a shaded tunnel of trees, going to Sedalia.

When that train car had been given to Windsor, according to the online article, the enterprising local antiquarians washed away the rust and grime of decades of accumulated use to reveal stars and stripes commemorating the “Spirit of ‘76”. “Adding even more intrigue,” the article goes on, “the original number of the caboose was discovered to be No. 76, not No. 130, as earlier thought.”

There was this one guy I talked to while resting by this haunted caboose, and the rain-proofed display offering a summary of its significance. In the scant seconds our interaction lasted, I felt like there was the largest transfer of information, verbal and non-verbal, of anyone I interacted with on the trip. After head nods and a few sentences, we quickly came to an understanding of who each other were.

I told him I’d walked from Clinton, and was looking for somewhere to camp. He told me about a guy named Dale, who you could rent cabins from, but also gave rather elaborate instructions about how to get to another place, behind the fair grounds, where you could camp for free.

“No, it’s okay,” I said. “I have a tent, and I don’t mind paying.” I could feel him trying to figure out why I would have walked on a bike trail, with a beat-up backpack dating from the last milleneum.

There were places around here, he told me, where I could buy a used bike for pretty cheap. Sedalia, he said, had a “healthier community.” I got the sense that he was talking about more than just an enthusiasm for cardio, that he was hinting, if I were the kind of scruffy drifter my appearance and clothes apparently suggested me to be, my luck might be better in the next town over.

“You walked from Clinton, but you’re not from Clinton, right?” He asked me.

“Nah, I’m from Kansas City, around there.”

“Me too,” the man said, and we went our separate ways.

I found Dale, who was harvesting some tomatoes from a garden, and traded him fifteen U.S. dollars for the right to pitch a tent in a charming little plot of wood-mulch with an antique bike chained to bales of hay. He also handed me a business card with the key code to the restroom, and the wi-fi password. The bathroom, critically, also had an electrical outlet where I could charge my phone.

The Tree

At the Dancing Rabbit Ecovillage, Alis loaned me a book called The Tree, by Colin Tudge. There was a letter in it, addressed to him. We’d talked about hiking, and I said I’d only ever really done day-hikes, camping overnight comprising a kind of line to the next level of outdoor adventuring I hadn’t been brave or resourceful enough to cross.

You can have a very detailed visual of the space where this conversation took place. There’s a PBS special, complete with drone footage, of where it happened (go to around 2:20).

The next time I saw him, I gave him back the letter, He told me it was from his father-in-law, around two years ago. He read parts of it out loud. “This is a day to celebrate,” the letter said, describing sitting at a fast food restaurant in Maryville. There was a side note with the exact number of the order.

We’d been talking about botanical illustrations, how they were more useful than photographs of species, because the ink could draw the eye to relevant details, rendering salient features, useful to identification in thicker or clearer lines.

“He’s drawing you a picture,” I said, talking about the letter. “He’s showing you the details he considers important.”

In the morning, the green tunnel to Sedalia filled with a foggy filter, the horse hooves of Amish horse-drawn buggies clattering on the streets, I went to a coffee shop called “The Pour Poet.” The cafe was also a used bookstore. I got a coffee and scone, and wrote Alis a message on a notecard, thinking I might slip it into the book when I gave it back to him. “It’s a day to celebrate!” I wrote. “Remember when I said, ‘I’ve only done day hikes’?”

The Library

The day before I left for my vacation, I did a “clean team” shift, where everyone in the ecovillage helps to clean the common house. “Do you want to do the library?” someone asked me. “It’s kind of a train wreck in there. You could put books back on the shelves, try to organize things.”

“There’s not enough room on the shelves for all the books,” I was telling people in the Ironweed kitchen later. “There’s no sorting, other than by type. There should be a way of ranking them, or featuring books we reccomend, a process to get rid of those no one will read.” This idea, of a library that didn’t just store books but sorted them, allowing for crowd-sourced ranking and annotation, has roots in many of my other preoccupations and projects. Collective knowledge that can evolve, like trees selected for certain traits.

I want to learn how to make recycled paper. The internet tells me you need a dedicated blender, and a frame with a screen. We could turn the unwanted, excess books from the library, the ones slated for removal by some distributed, democratic process, into drawing paper, or greeting cards. You could write reviews on them of the surviving books, or little notes to future readers, and slip them between the pages.

Equipment

I have a heavy, internal frame backpack that I got back in 2000, before going to Romania with the Peace Corps. We’ve been through a lot together.

For shoes, I was wearing some old running shoes I’d ordered online, with holes on the top front where the nails of my big toes have worn through the fabric.

My tent was the only thing I’d recently purchased, an investment to push me through the barrier from a mere day-hiker to someone who isn’t afraid to dream outside. Two person, but small. One of the first rules or recommendations I saw posted on the hike was Try to avoid hiking the Katy Trail alone. “I tried,” I thought to the sign.

For food, I’d packed a plastic bag of cranberries and walnuts, another of granola, a jar of peanut butter, and chopsticks. My plan was to dip the chopsticks in peanut butter, and then in granola, but this proved impracticable.

The first stretch of the trail, from Clinton to Calhoun, was unlovely, running next to a state highway, a thin curtain of trees, grass, and wildflowers doing little to obscure the sight or sound of traffic. Yet, such is Missouri, or the midwest in general, these stitches of asphalt somehow containing the immensity of fields and farms, attenuating imagination like blinders on a horse.

On the way out, the sky was cloudy, and the novelty of the ground passing under me made the miles go quickly. On the way back, my shoulders chafed from the straps, my legs sore and toe blistered, there were long shadeless stretches, punctuated with skinks, grasshoppers, and dragonflies.

That first day, when I got to Calhoun I was encouraged by reaching the more-or-less midway point so quickly, and got a couple of IPAs from a gas station, drinking them as I walked. The great thing about doing things alone is no one is there to question your decisions.

The internet, when I was planning the walk, told me that a normal hiker could cover 8 to 10 miles per day, with 12-16 on the high end. The distance from Clinton to Windsor, the nearest campsite, was 16.6 miles, and camping was not allowed on the trail.

That was the adventure, the risk and discomfort I could subject myself to, because I was alone, and not responsible for anyone else’s safety or well-being.

Selfie

I walked the Katy Trail in order to write about it. Also as a way to imagine, or promise myself, even longer hikes, more rambling letters and stories.

When I got back to Clinton, relieved to see my father’s truck still in the lot by the trail head, I went to the Pizza Glen to celebrate, reveling in the air-conditioned nostalgia of cloudy red cups and a Cruis’n arcade game, listening to the manager show genuine interest in her employee’s lives. I was the only customer, except for people collecting take-out.

Was I satisfied? There had been other, more grandiose plans for the two weeks I’d taken off work, blocked by various logistical challenges. Really, that one night under the stars, those two days of hard walking, were all I needed to hang my hero’s journey on.

In the restaurant, eating a “deep dish” pizza (just a normal, not-that-great pizza with a slightly thicker crust), my body and clothes smelling of miles of unshowered sweat, legs so sore I was waddling more than walking, I felt like it was, for then, enough.